Study

Guide

Study

Guide

Histology of the

Gastrointestinal System

SAQ -- Questions and slides available for self-assessment (and advanced learning).

Study Guide

Histology of the

Gastrointestinal System

SAQ -- Questions and slides available for self-assessment (and advanced learning).

The histology of the entire gastrointestinal tract is largely the histology of epithelial tissues.

The mucosal epithelium is highly differentiated along the several regions of the GI tract.

At the upper and lower ends of the tract, the epithelium is protective, stratified squamous.

This protective epithelium is partially keratinized on the hard palate and gums and on the tips of filiform papillae of the tongue. Elsewhere in the oral cavity, esophagus, and anal canal the epithelium is non-keratinized.

Along the lining of the stomach, small intestine, and colon, the epithelium is simple columnar.

Each region contains certain specialized cell types which are adapted to carry out the region's characteristic functions of secretion and absorption.

Tissue Layers of the GI Tract

The GI tract is essentially a tube extending from the oral cavity to the anus. This tube is organized into a series of four distinct layers which are fairly consistent throughout its length. (Click on a link for more detail, or scroll down.)

Cautionary note: Terms such as inside and outside are potentially confusing when used to describe tubular organs. Context is critical. Most commonly, inside refers to the lumen of the organ, while outside refers to the portion farthest away from the lumen (i.e., most deeply inside the body). However, this usage is often inverted when referring to a mucosal epithelium, so that outside refers to the apical surface of the epithelium while inside refers to the basal, connective tissue side.

Less ambiguous are the "proper" terms adluminal (toward the lumen) and abluminal (away from the lumen). Unfortunately, these proper terms are so similar to one another in both spelling and pronunciation that they too are easily confused (and therefore seldom used).

Proceeding from the inside (i.e., abluminally from the lumen):

- Mucosa -- innermost layer (closest to the lumen), the soft, squishy lining of the tract, consisting of epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae.

- Submucosa -- connective tissue supporting (outside, deep to) the mucosa.

- Muscularis externa -- muscular wall of the tract, surrounding (outside, deep to) the submucosa.

- Adventitia / serosa -- outermost layer (deepest, farthest from the lumen) is called either adventitia (in regions where the tube passes through the body wall) or serosa (in regions where the tube passes through body cavities).

The mucosa is the inner layer of any epithelially-lined hollow organ (e.g., mouth, gut, uterus, trachea, bladder, etc.). The mucosa consists of the epithelium itself and also the supporting loose connective tissue, called lamina propria, immediately beneath the epithelium. Deeper connective tissue which supports the mucosa is called the submucosa. In the GI tract (but not in other tubular organs), there is a thin layer of smooth muscle, the muscularis mucosae, at the boundary between mucosa and submucosa.

The mucosa is the most highly differentiated layer of the GI tract. Tissue specialization and surface shape are correlated with functional differentiation along the tract.

Oral cavity-- Epithelium is protective (stratified squamous, partially keratinized on gums and hard palate and on filiform papillae of tongue, non-keratinized elsewhere). Lamina propria is unspecialized. A muscularis mucosae is not present.

Oral cavity-- Epithelium is protective (stratified squamous, partially keratinized on gums and hard palate and on filiform papillae of tongue, non-keratinized elsewhere). Lamina propria is unspecialized. A muscularis mucosae is not present.

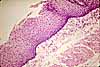

Esophagus -- Epithelium is protective (stratified squamous, non-keratinized). Lamina propria is unspecialized. Muscularis mucosae consists of scattered bundles of longitudinal muscle fibers.

Stomach -- The gastric mucosa is specialized for production of digestive acid and enzymes. The mucosal surface of simple columnar epithelium consists of mucus-secreting cells for protection against self-digestion. The bulk of this thick mucosa is occupied by acid-secreting cells and enzyme secreting cells which comprise closely-packed glands within the gastric mucosa. Lamina propria is inconspicuous, filling the interstices between the tubular gastric glands. Muscularis mucosae is thin.

Small intestine -- The intestinal mucosa is specialized for absorption of nutrients and is thereby delicate and vulnerable. The simple columnar epithelium consists of absorptive cells (enterocytes) with scattered goblet cells (which secrete mucus for lubrication). Surface area is vastly increased via evaginating villi. Invaginating crypts contain stem cells for ongoing replenishment of the epithelium. Lamina propria occupies the cores of villi, envelops crypts, and includes numerous immune cells. Smooth muscle fibers may extend into villi. Muscularis mucosae is thin.

Appendix -- Mucosa is similar to that of colon, but with more lymphoid tissue. Absorptive and secretory epithelium (simple columnar) is shaped into crypts (no villi). Lamina propria surrounds the crypts and contains many lymph nodules. Muscularis mucosae is thin.

Colon (and rectum) -- Absorptive and secretory epithelium (simple columnar) is shaped into crypts (no villi). Lamina propria surrounds crypts (i.e., fills the interstices between them). Muscularis mucosae is thin.

Anal canal -- Epithelium is protective (nonkeratinized statified squamous) with transition to epidermis (keratinized). Lamina propria is unspecialized with transition to dermis. Muscularis mucosae ends at recto-anal junction.

Lamina propria is loose connective tissue in a mucosa. Lamina propria supports the delicate mucosal epithelium, allows the epithelium to move freely with respect to deeper structures, and provides for immune defense. Compared to other loose connective tissue, lamina propria is relatively cellular. It has been called "connective tissue with lymphatic tendencies."

Because mucosal epithelium is relatively delicate and vulnerable (i.e., rather easily breached by potential invading microorganisms, compared to epidermis), lamina propria contains numerous cells with immune function to provide an effective secondary line of defense.

At scattered sites along the tract, lamina propria may be heavily infiltrated with lymphocytes and may include lymph nodules (i.e., germinal centers where lymphocytes proliferate). Such sites are especially characteristic of tonsils, Peyer's patches (in ileum), and appendix, but may occur anywhere.

Accumulations of lymphoid tissue may be reminiscent of inflammation (e.g., the mucosa of a chronically inflamed colon may resemble that of a normal appendix).

Lamina propria contains most of the elements of ordinary connective tissue.

- Lamina propria is generally not as fibrous as the deeper connective tissue of submucosa.

- Lamina propria has a relatively high proportion of lymphocytes and other immune cells.

- Lamina propria has practically no fat cells.

- Lamina propria includes a rich bed of capillaries.

(Capillaries are usually inconspicuous in standard histological specimens, but they are nicely displayed in the image (thumbnail to right) of a vascular preparation of stomach mucosa.)- In the small intestine, lamina propria of villi includes lacteals (lymphatic capillaries).

- Lamina propria of intestinal villi may include smooth muscle fibers.

In the oral cavity and esophagus, lamina propria is located immediately beneath a stratified squamous epithelium. Lamina propria beneath such a protective epithelium is usually less cellular (fewer lymphocytes) than elsewhere.

Where the mucosal epithelium is extensively evaginated (e.g., intestinal villi) or invaginated (intestinal crypts), the location of lamina propria "beneath" the epithelium amounts to filling-in between nearby epithelial surfaces (i.e., surrounding each crypt, within each villus). Where epithelial invaginations are densely packed (e.g., gastric glands of stomach), lamina propria can be relatively inconspicuous.

The muscularis mucosae is a thin layer of smooth muscle at the boundary between mucosa and submucosa. It occurs throughout the GI tract from esophagus to rectum. It is thickest in esophagus, where it consists of relatively conspicuous bundles of longitudinal muscle fibers. The muscularis mucosae is thinner in the rest of the tract (stomach, small intestine, colon), although it contains both circular and longitudinal fibers.

Functionally, the muscularis mucosae is not well studied. Presumably it functions to promote local stirring at the mucosal surface, to improve secretion and the absorption of nutrients.

The submucosa is a connective tissue layer deep to and supporting the mucosa.

The substance of the submucosa is ordinary loose connective tissue. It allows the mucosa to move flexibly during peristalsis.

Try this to explore the mechanical quality of the submucosa: Hold the inner lining (mucosa) of one cheek between your teeth, and pinch the skin of that cheek with your fingers. Now, feel how these two layers move freely past one another (up to a point), even though they are bound together by loose connective tissue.

Motility can be reduced by excess fibrous tissue in the submucosa, such as that produced in scleroderma. (For more, go to WebPath or see Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease.)

The submucosa contains a vascular plexus, relatively large veins and arteries which give rise to the capillary bed of the mucosa.

The submucosa also includes a delicate nerve network, called Meissner's plexus (or the submucosal plexus).

Submucosal glands occur in two regions of the tract:

The esophagus has occasional submucosal mucous glands. The submucosa of the

duodenum is densely

packed with mucous

Brunner's glands.Otherwise, the submucosa has similar characteristics throughout the tract.

The muscularis externa ("muscularis" for short) is the muscular wall of the GI tract, deep to (surrounding) the submucosa.

The tongue and the muscularis of the upper esophagus consists of striated muscle.

Along the rest of the tract, the muscularis consists of two distinct layers of smooth muscle.

The inner circular layer consists of smooth muscle fibers wrapped around the long axis of the tract.

The outer longitudinal layer consists of smooth muscle fibers extending along the long axis of the tract.

More precisely, muscle fibers in both layers spiral around the tract, either at a very shallow angle (the circular fibers) or a much steeper angle (the longitudinal fibers).

The muscularis of the stomach is thicker than that elsewhere, with the muscle fibers layered in more orientations (often described as assuming three layers, which are not readily distinguishable in routine sections).

In the colon, the longitudinal muscle is gathered into three longitudinal bands, the taenia coli.

Between the two muscle layers lies Auerbach's plexus of parasympathetic nervous tissue. Coordinated contraction of these layers is responsible for rhythmic peristalsis.

The adventitia or the serosa is the outermost (i.e., most distant from the lumen) layer of the GI tract.

When the outermost layer is attached to surrounding tissue, it is called adventitia.

- Adventitia is just ordinary fibrous connective tissue arranged around the organ which it supports.

When the outermost layer lies adjacent to the peritoneal cavity, it is called serosa.

- The serosa consists of ordinary connective tissue with a surface of mesothelium.

- Serosa has the same composition as mesentery.

- The serosa comprises the visceral peritoneum. It continues over the abdominal wall as the parietal peritoneum

Mesothelium is a simple squamous epithelial tissue which forms the surface of the serosa in the major body cavities (peritoneal, pleural, and pericardial).

Mesentery is connective tissue which binds together the loops of the GI tract. Mesenteries have the same composition as serosa and, like the serosa, and are covered on exposed faces by mesothelium.

Regions of the GI tract

Each region of the GI tract is structurally and functionally differentiated, with features of cell specialization and tissue arrangement (especially of epithelial tissues) which serve local function.

The upper tract is specialized for sensory discrimination (taste), mechanical processing (chewing), initial lubrication and enzymatic digestion (salivary secretion), and immune surveillance (tonsils), with a protective stratified squamous epithelium throughout.

Specialized subdivisions include tongue, teeth [no link for teeth; we leave teeth to the dentists], hard and soft palate, salivary glands, tonsils.

The esophagus provides passage between the oral cavity to the stomach. Compared to other regions of the GI tract, the esophagus is a fairly simple tube lined by a stratified squamous epithelium. Functional specializations are correspondingly few.

The stomach is specialized for secretion of digestive enzymes and acid, for mechanical stirring, and for protecting itself against self-digestion.

The small intestine is specialized for absorption of nutrients.

Subdivisions of the small intestine include duodenum (with Brunner's glands, specialized for neutralizing stomach acid), jejunum, and ileum.

The pancreas is a gland specialized for relatively massive secretion of digestive enzymes into the small intestine at the junction between duodenum and jejunum.

The liver has a unique pattern of epithelial cell organization, specialized BOTH for filtration of blood (all blood from the intestine and spleen passes through the liver before returning to general circulation) AND for bile secretion.

The lower tract is specialized for continued absorption of nutrients and for concentration of undigested material by reabsorption of water.

Subdivisions of the lower tract include appendix, colon, rectum, and anal canal.

Link to Specialized Cell Types

Special Features of Histological Organization

Special Features of Surface Shape

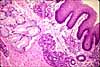

Villi are very small, typically densely-packed, evaginations of a mucosa. (The word villus shares the same root as velvet.) In the small intestine, villi contribute an order-of-magnitude increase in the mucosal surface area available for absorption.

Villi characterize the mucosa of the small intestine throughout its length.

The varying shapes of villi --which may be finger-shaped, flattened, or ridge-like -- are most easily appreciated in tangential sections of the intestinal mucosa.

Each intestinal villus has a surface of simple columnar epithelium (absorptive cells and goblet cells) and a core of lamina propria. In addition to the loose, cellular connective tissue that is typical of lamina propria throughout the gut, villi also contain capillaries, lacteals and smooth muscle fibers.

Appearance of villi and crypts.

In section, a villus is outlined by a ring of epithelium surrounding a core of lamina propria. Empty space surrounds each villus.

Crypts, in contrast, are surrounded by lamina propria. The epithelium surrounds a central lumen.

Image © Blue Histology

Crypts are short invaginations of mucosal epithelium. Crypts provide protected pockets for special cellular functions.

Tonsilar crypts occur in the palate, the pharynx, and the back of the tongue.

- Tonsilar crypts provide sites where immune surveillance cells (lymphocytes) can encounter foreign antigens which are entering the body through the oral cavity.

- Tonsilar crypts are surrounded by lymphoid tissue, with well-developed germinal centers. The entire structure (crypt, epithelium, and lymph nodules) is called a tonsil.

Intestinal crypts are characteristic of both small intestine (where they occur between the villi) and of appendix, colon, and rectum (where crypts are not associated with villi).

- Intestinal crypts are sometimes called "intestinal glands" (they have the shape of short, straight, simple tubular glands).

- They are also commonly called crypts of Lieberkühn.

Historical note: Crypts of Lieberkühn are named for Theodor Lieberkühn (b. 1711).

Intestinal crypts contain secretory Paneth cells (named for Joseph Paneth, b. 1857) at the deep end. These cells secrete lysosomal enzymes, which contribute to protecting the stem cells in the crypt lining.

Undifferentiated stem cells located along the length of intestinal crypts give rise to new absorptive cells and goblet cells. The entire surface epithelium of the intestine is replaced every few days, by new cells arising from the crypts.

Appearance of villi and crypts.

In section, a villus is outlined by a ring of epithelium surrounding a core of lamina propria. Empty space surrounds each villus.

Crypts, in contrast, are surrounded by lamina propria. The epithelium surrounds a central lumen.

Image © Blue Histology

A plica is a fold (plural plicae; the word shares the same derivation as the word "pleat"). Plicae of the small intestine are permanent folds in the mucosa supported by a core of submucosa. Plicae increase the absorptive surface area of the mucosa, while also obliging the intestinal contents to pursue a more tortuous path down the intestinal lumen.

Historical note: Intestinal plicae are also called valves of Kerckring, named after Theodor Kerckring, b. 1638.

A papilla is a small protuberance. In the GI system, the word is used to describe the various small projections on the surface of the tongue.

A gastric pit is a shallow indentation in the surface epithelium of the stomach mucosa. These pits, which are lined by a protective epithelium of surface mucous cells, confer a characteristic texture to the entire surface of the stomach. Gastric glands open into the bottoms of the pits.

Lymphatic Features

For more about the immune system, including outside links, see CRR Lymphatic System.

Lymphoid tissue occurs in lamina propria all along the GI tract, where it is sometimes referred to as GALT, for Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue, or MALT for Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissues.

The most characteristic feature of gut-associate lymphoid tissue is the presence of clusters of lymph nodules (also called lymphoid follicles), which are sites where lymphocytes congregate. At the center of each lymph nodule is a "germinal center" where the lymphocytes proliferate.

The connective tissue around a lymph nodule is usually heavily infiltrated with lymphocytes migrating to and from the germinal center.

Lymph nodules may occur in lamina propria anywhere along the GI tract. Thousands of individual lymphoid nodules may occur along the small and large intestine. Masses of lymphoid tissue may extend beyond lamina propria and intrude into the submucosa. Nearby epithelial tissue may also be infiltrated by lymphocytes.

Aggregations of lymph nodules are characteristic of tonsils, Peyer's patches of ileum, and appendix.

For more on gut-associated lymphoid tissues, consult your histology text.

For a recent research perspective, see "Immunity, Inflammation, and Allergy in the Gut," Science 307:1920 (2005).

Tonsils are lymphoid structures located in the mucosa of the tongue, palate, and pharynx. Each tonsil consists of an epithelial crypt (invaginated pocket) surrounded by dense clusters of lymph nodules. Tonsils provide sites where immune surveillance cells (lymphocytes) can encounter foreign antigens which are entering the body through the oral cavity.

For more on "Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissues" (GALT, or MALT for Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissues), consult your histology text.

Peyer's patches are lymphoid structures located in the mucosa of the ileum.

Historical note: Peyer's patches are named for Johann Conrad Peyer, a 17th Century Swiss anatomist who first described these structures in 1677.

Each patch consists of a cluster of lymph nodules which bulge upward toward the lumen. The surface epithelium of Peyer's patches is formed by low cuboidal M-cells, specialized enterocytes which facilitate interaction between antigen and lymphocytes. (For a somewhat dated review of M-cell biology, see Gut (2000) 47:735)

For more on "Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissues" (GALT, or MALT for Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissues), consult your histology text. For a recent research perspective, see "Immunity, Inflammation, and Allergy in the Gut," Science 307:1920 (2005).

Lacteals are lymphatic channels in each of the villi of the small intestine. Lacteals provide passage for absorbed fat (the chylomicrons) into the lymphatic drainage of the intestine.

For more about the immune system, including outside links, see CRR Lymphatic System.

Basic Tissues

Connective tissues associated with the gut are rather unspecialized, with the exception of lymphoid tissues specialized for immune function. Nevertheless, the ordinary loose connective tissues of lamina propria, submucosa, and serosa perform vital functions of transport and mechanical support (as well as being involved in inflammation). Be sure you are familiar with the basic components and functions of connective tissue.

In solid organs such as glands, the connective tissue along with associated blood vessels and ducts is often referred to as stroma.

When examining a slide of any organ, pay attention to the connective tissue. The signs of inflammation appear in connective tissue. To detect such signs, you must first be familiar with the normal (i.e., uninteresting) appearance.

Nervous Tissue

The gastrointestinal system is well-supplied with both sensory and motor innervation. Along the tract, this nervous tissue is concentrated into Auerbach's and Meissner's plexus. Each plexus comprises a network of unmyelinated nerve fibers (generally inconspicuous) and associated ganglia.

The nerve cell bodies which cluster into the parasympathetic ganglia of Auerbach's and Meissner's plexus are easily observed microscopically.

Each nerve cell body can be quite large (up to ~50µm), with relatively basophilic cytoplasm and with a large, round, euchromatic nucleus with a single prominent nucleolus.

Associated with peripheral ganglia are numerous small satellite cells and Schwann cells, as well as fibroblasts of the surrounding connective tissue.

Auerbach's plexus is located between the circular and longitudinal smooth muscle layers of the muscularis externa. (The name commemorates Leopold Auerbach, b. 1828.) Coordinated contraction of these layers is responsible for rhythmic peristalsis.

Auerbach's plexus is also called the myenteric plexus (from myo- muscle, and enteron, gut)

Meissner's plexus is located within the submucosa. (The name commemorates Georg Meissner, b. 1829.) Neurons in this plexus influence the smooth muscle of the muscularis mucosae, including the smooth muscle fibers which extend into intestinal villi.

Meissner's plexus is also called the submucosal plexus.

The parasympathetic ganglia of Meissner's plexus are less common and smaller (fewer nerve cell bodies) than those of Auerbach's plexus. If you happen to notice a large cell with basophilic cytoplasm, a round euchromatic nucleus, and a prominent nucleolus, located in the submucosa, then you've seen a neuron of Meissner's plexus.

For more on nerve cells generally, see neuron or "Cells 'R' Us".

Muscle Tissue

Striated muscle comprises the bulk of the tongue, as well as the muscularis of the upper esophagus.

Throughout the rest of the GI tract, smooth muscle forms a substantial two-layered muscularis externa.

Smooth muscle also forms a delicate muscularis mucosae at the deep boundary of the mucosa (i.e., between lamina propria and submucosa).

Unlike striated muscle, smooth muscle consists of individual cells, each cell with its own nucleus. The function of smooth muscle also differs substantially from that of striated muscle. (More.)

Each smooth muscle cell (or "muscle fiber") is very long and narrow, up to several hundred micrometers in length but just a few micrometers in diameter. The nucleus is also elongated. (More.)

Comments and questions: dgking@siu.edu

SIUC / School

of Medicine / Anatomy / David

King

https://histology.siu.edu/erg/giguide.htm

Last updated: 14 June 2022 / dgk